2025 has been a tumultuous year for international trade, marked by uncertainty. Recent trade policies initiated by the Trump administration and the retaliatory measures by trading partners are causing significant shifts in global trade dynamics.

One of the sectors most affected is the grain and soybean trade, which has become a focal point in the tensions between the US and China. China is the largest importer of US grains and soybeans, and they accounted for 40% of the exported volumes in 2022. Naturally, these trades are likely to have drastic effects on the grain and soybean trade; however, this is not the first time such tensions have arisen, and China appears to be better prepared this time.

The evolution of US-China grain and soybean trade

Using AIS data from Oceanbolt, Veson’s port, tonnage, and commodity analytics solution, tracking ship movements between the two countries, we identify that China has been decoupling from US grain and soybeans the last couple of years, long before the recent tariff announcements. So far in 2025, China’s imports of US grain and soybeans totalled 6.6 million metric tons, marking a significant 72% decline from the peak trade levels observed in 2021.

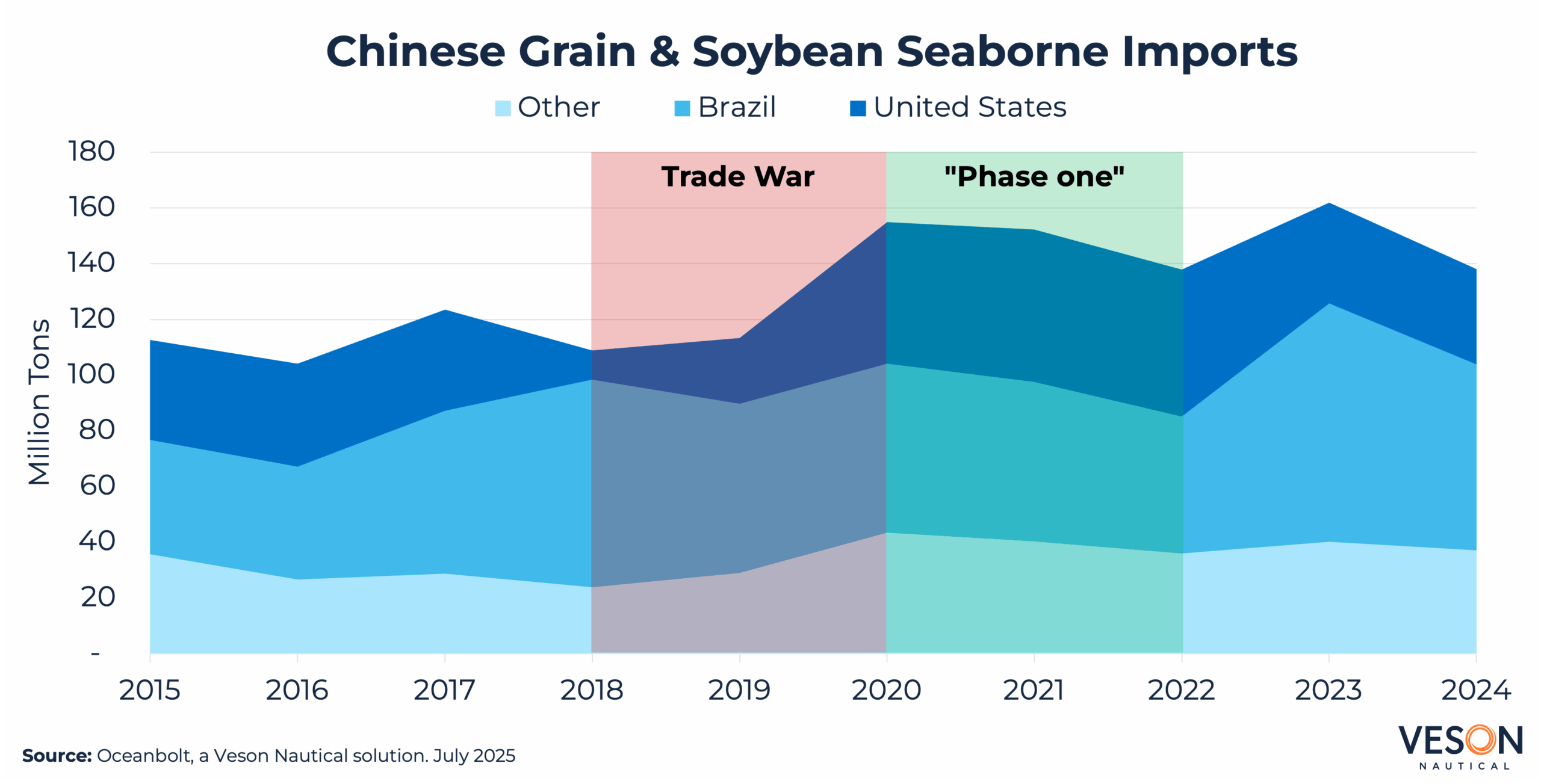

During the first Trump administration, a trade war erupted between the US and China in July 2018 when the US imposed a 25% tariff on $34 billion worth of Chinese goods, primarily targeting industrial and technological products. China retaliated with a 25% tariff on $34 billion worth of US goods, including soybeans, corn, and other agricultural products. This marked the beginning of a tit-for-tat trade war that escalated over the following months, eventually targeting $550 billion of Chinese goods and $185 billion of US goods.

Before the trade war, from 2015 to 2017, China imported an average of 36.4 million tons of grain and soybeans annually from the US, with the US supplying 32% of China’s grain imports; however, during the trade war, China significantly reduced its imports of US grain and soybeans, with volumes halving to an average of 17.1 million tons per year. During this period, the US accounted for only 15% of China’s grain and soybean imports, as China increased imports from Brazil instead.

After approximately 1.5 years of trade wars, negotiations began to yield results, and in early 2020, a “phase-one deal” was agreed upon. China committed to purchasing at least $200 billion worth of US goods and services more than it did in 2017, while the US reduced tariffs on certain Chinese imports and cancelled further scheduled duties. The “phase-one deal” not only normalized US-China grain and soybean trade but also led to a significant increase, with China importing an average of 52.8 million tons per year during 2020-2022. This represents a 45% increase from pre-trade-war levels. During these years, the US accounted for 36% of China’s grain and soybean imports, regaining market share.

However, the US eventually lost market share as trade negotiations stalled. In 2023 and 2024, China imported an average of 35.2 million tons of grain and soybeans from the US, a 33% decline from the “phase-one” levels. Consequently, the US market share fell to 24%. Meanwhile, trade relations between China and Brazil were improving significantly. The two countries signed 20 agreements to expand bilateral trade and Brazil’s president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva visited China in 2023. Most notably these agreements facilitated exports of corn and sorghum from Brazil to China. Subsequently, China increased its imports of Brazilian grain and soybeans to an average of 76.2 million tons per year during 2023-2024, a 37% increase from the 2020-2022 levels. This boosted Brazil’s market share from 38% to 51%.

China’s strategic pivot toward Brazilian grain and soybeans

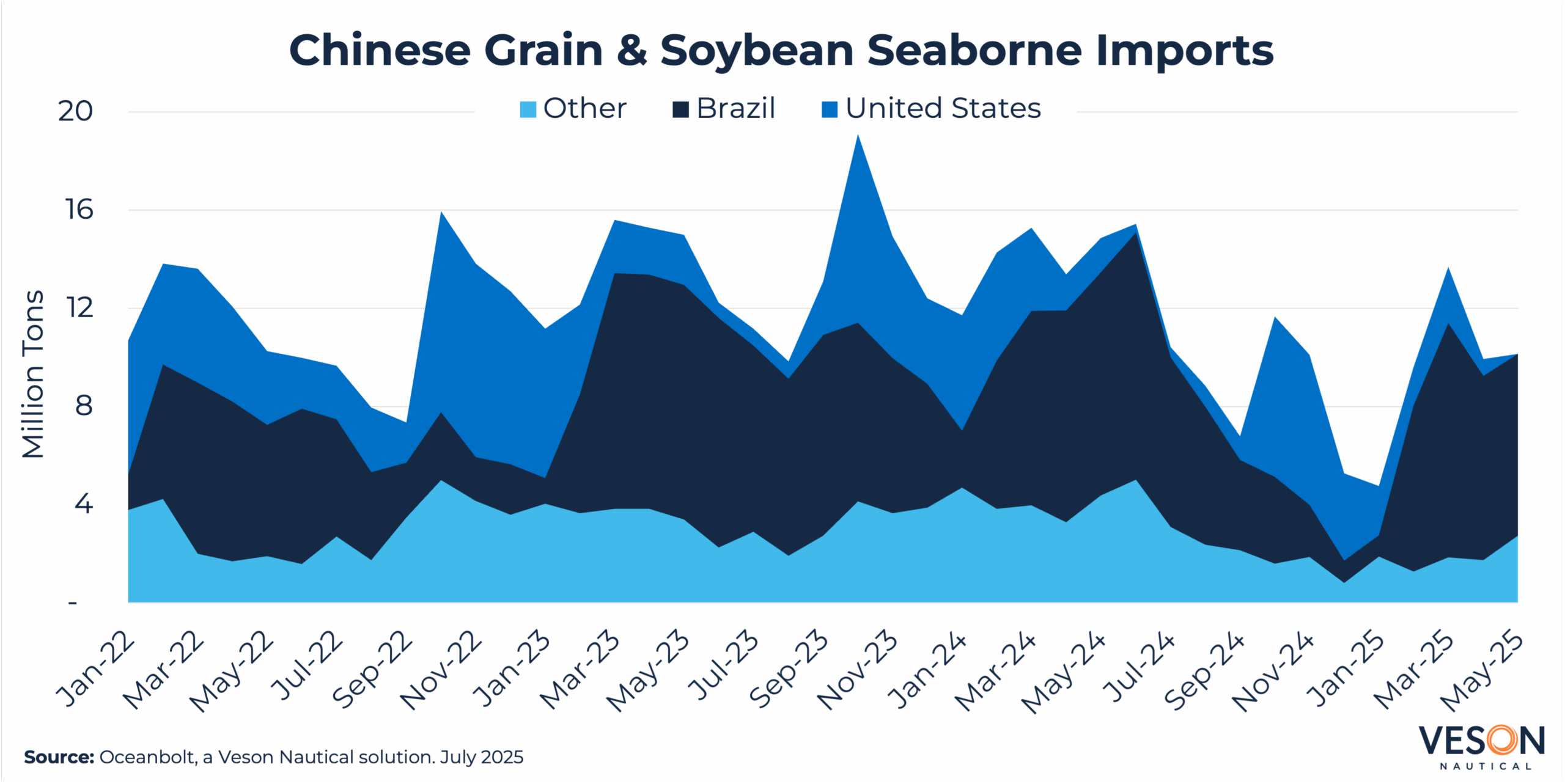

China appears to have been positioning themselves for a potential trade war the last two years, as they have been decoupling more and more from the US in the grain and soybean trades. This trend has continued into 2025, as Chinese imports of US grain and soybeans so far this year fell 57% from the same period last year. It is important to note that some of this decline stems from the total grain imports to China declining 31% during the same period, as they had record domestic crops last year. However, the market share of US grains in China declined from 22% January-May 2024 to 14% during the same period this year, while the Brazilian share increased from 49% to 67%.

Considering the current trade disputes and the improving relations between China and Brazil, it is likely that China will continue their shift from US to Brazilian grain and soybean supplies. Even though a 90-day truce has been agreed between the US and China, the US grain and soybean exports will still be subject to 10% tariffs—and a high degree of uncertainty remains around what will happen after the 90 days. Meanwhile, President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and Xi Jinping signed another 20 deals during Lula`s visit to China in May this year, including further agreements on agricultural exports. Both countries stated that they are seeking to strengthen their ties in an increasingly uncertain world. This indicates that the Chinese imports of grain and soybean from Brazil will continue growing.

Using data from Shipfix, Veson’s AI-powered data and communication workflow solution, we can anticipate that this trend will likely persist over the next few months. Shipfix collects information on cargoes and vessels active in the market. Typically, most cargoes are in circulation within one month of the loading date, and it usually takes over 30 days for cargo to reach its destination, depending on the sailing distance. Consequently, Shipfix provides a forward-looking perspective on expected imports for the upcoming months, based on the volume of cargoes in circulation. In May 2025, the volume of grain cargoes in circulation from the US to China was 72% lower than in May of the previous year. This suggests a substantial decrease in grain imports from the US to China in the coming months.

The impact of longer routes and higher rates on dry bulk shipping

The seismic shifts in China’s grain supplies are poised to significantly impact grain trade dynamics. From a shipowner’s perspective, there may be short-term benefits. According to Oceanbolt data, the average sailing distance for grain cargoes from the US to China is 10,091 nautical miles, whereas from Brazil to China, it is 13% longer at 11,400 nautical miles. An increase in Brazilian grain volumes would extend sailing distances, thereby supporting demand for shipping capacity and improving freight rates. A sudden surge in demand for Brazilian grains could also strain the supply chain, causing congestion and inefficiencies that limit vessel availability, potentially strengthening the shipping market further.

However, the long-term outlook appears more concerning. As China diversifies its grain sources, prices for non-US grains are likely to rise. Consequently, China may face a choice between purchasing US grains with a 10% tariff or buying non-US grains at elevated prices. In either scenario, they will encounter higher costs than in the absence of trade barriers, potentially leading to reduced demand. This could result in a decline in overall grain trade, negatively affecting exporters, importers, and shippers alike.

Fortunately, the dark clouds in global trade have coincided with favourable weather in South America. Brazil’s National Supply Company (CONAB) anticipates record grain production in the 2024-2025 season, projecting total output to reach 332.9 million tonnes—a 10.6% increase from the previous year. This growth is primarily driven by robust soybean and corn production. The strong production is expected to mitigate the initial impact of tariffs, as the grain market remains well-supplied, allowing China to easily shift to Brazilian sources. However, this may not hold true in years with poor harvests.

Grain crops are highly susceptible to sudden weather changes, and adverse conditions can significantly reduce grain and soybean yields. Combined with tariffs, low production could lead to substantially higher prices, further dampening demand and international trade. With global warming likely to cause more extreme weather in the future, the grain and soybean markets may face a turbulent path ahead.